Suddenly, the perspective shifts when I’m writing in my journal—no longer I but you. The second person takes over. I continue moving my hand along the page, but a consciousness outside my own subordinates me, treats me as you. But who is I or you or me? Who’s in control…who’s not?

The second person doesn’t know me well enough to narrate my life: It may reveal glimpses of my past, but it doesn’t see the future before I do. These limitations make this point of view good for stories where the narrator needs to be as close as possible to the protagonist without actually being them. But it subordinates the protagonist with its instructional tone. In Lorrie Moore’s essay “How to Become a Writer,” the second person is Moore’s present self looking back on her journey as a young writer and guiding that person through it based on the conclusions she’s made over the years.

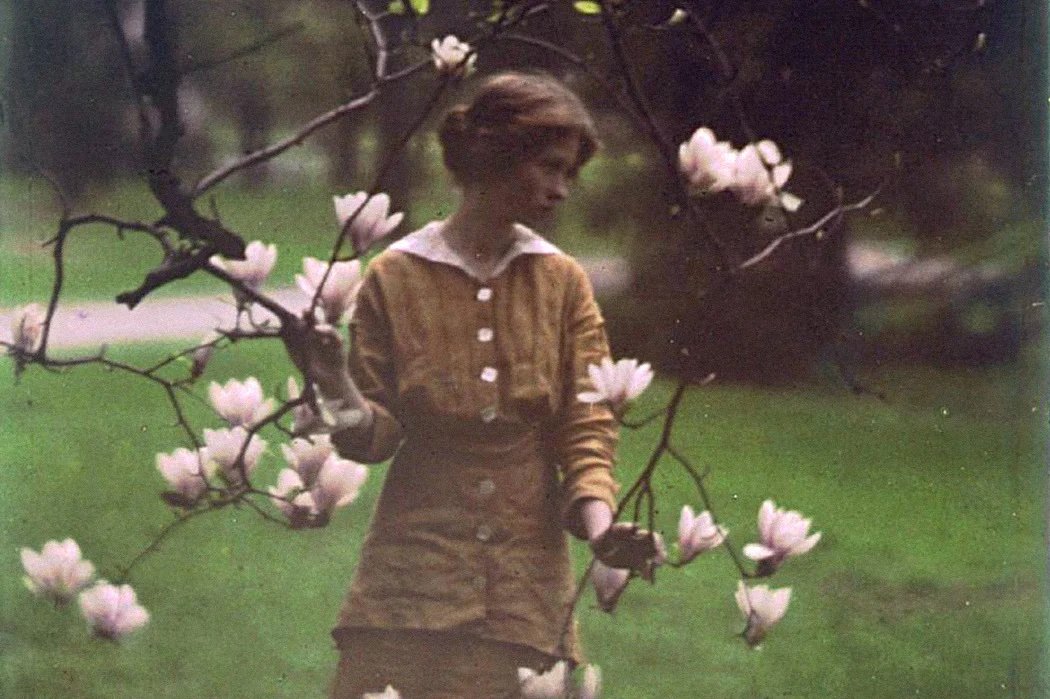

Through the second person, perhaps one can make peace with past selves.

What shows up in my journal, though, is more present, more urgent. Less a voice of experience than one of punishment. Punishing me for what, you might ask. Punishing me for who I am not. Nowhere is this voice more prominent than in my lists, a format where I will no longer do. These lists are usually about what I must do, and what I’m not doing. Who I am, and who I am not. The you aims to be a bridge of self-improvement. In the many lists of books and films and art works I hope to read, watch, and see, “you must” could be read before each one, even when absent. Instructions from the second person.

But where do I go?

It’s not that I disappear…I just become I, etcetera, like the title of Susan Sontag’s 1978 short story collection. The narrative voice in each story is disembodied, struggling to place events in a coherent flow for the reader (and the writer herself). I know from Benjamin Moser’s brilliant biography of Sontag that she demanded self-improvement. She sought to bridge the gaps between the many versions of Susan Sontag. She sought to bridge the gap between the writer she was and the writer she wanted to be—not become but be.

Sontag was a master of lists. She knew when they were needed in her work and could drill any subject down into items grouped based on some loose relationship they have to one another. A list is a body in how it brings together limbs of thought. Sontag wouldn’t approve of that metaphor. But she’s attempting to bring together disparate things in her lists. “Somewhere, some place inside myself, I am detached” (24) she writes in her short story “Project for a Trip to China,” which could almost be read as literary nonfiction.

“Somewhere, some place inside myself, I am detached.” — Susan Sontag

There are at least 42 different lists in “Project for a Trip to China,” though the entire story could really be read as a list. Sontag is trying to distill this trip down to an itinerary based on memory, imagination, and history. Finally, she will be able to link her imagined China (a place tied to her father, who she never knew) and the real China. “Mythical voyage” (27). Her trip will result in “literature” more than “knowledge.”

In our personal writing, can we be both the psychoanalyst and the patient? Sontag’s feelings about psychoanalysis were that we tend to rely on it too much. We seek a reason for why we want to go to China and what that trip would mean to us before we even go. We overanalyze for meaning, interpret instead of experience; and as the title of her famous essay collection makes clear, Sontag was Against Interpretation. But in “China,” I wonder if she’s trying to bridge analyst and patient, and that’s the project that fails in the end: “Perhaps I will write the book about my trip to China before I go” (29).

Literature over knowledge.

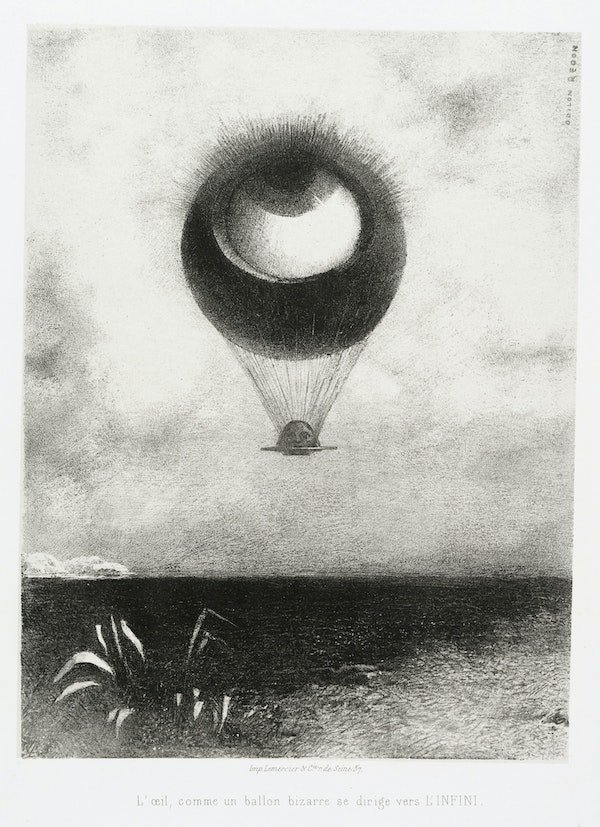

The limitations of the second person come from the directions this point of view gives the protagonist. You not I. I, etcetera, which doesn’t mean “I, plus” or “I, and so on.” It only means that the I is constantly being overthrown. Overthrown by a narrative consciousness that analyzes and interprets experiences for me.

The second person takes over.