The roots I'm putting down

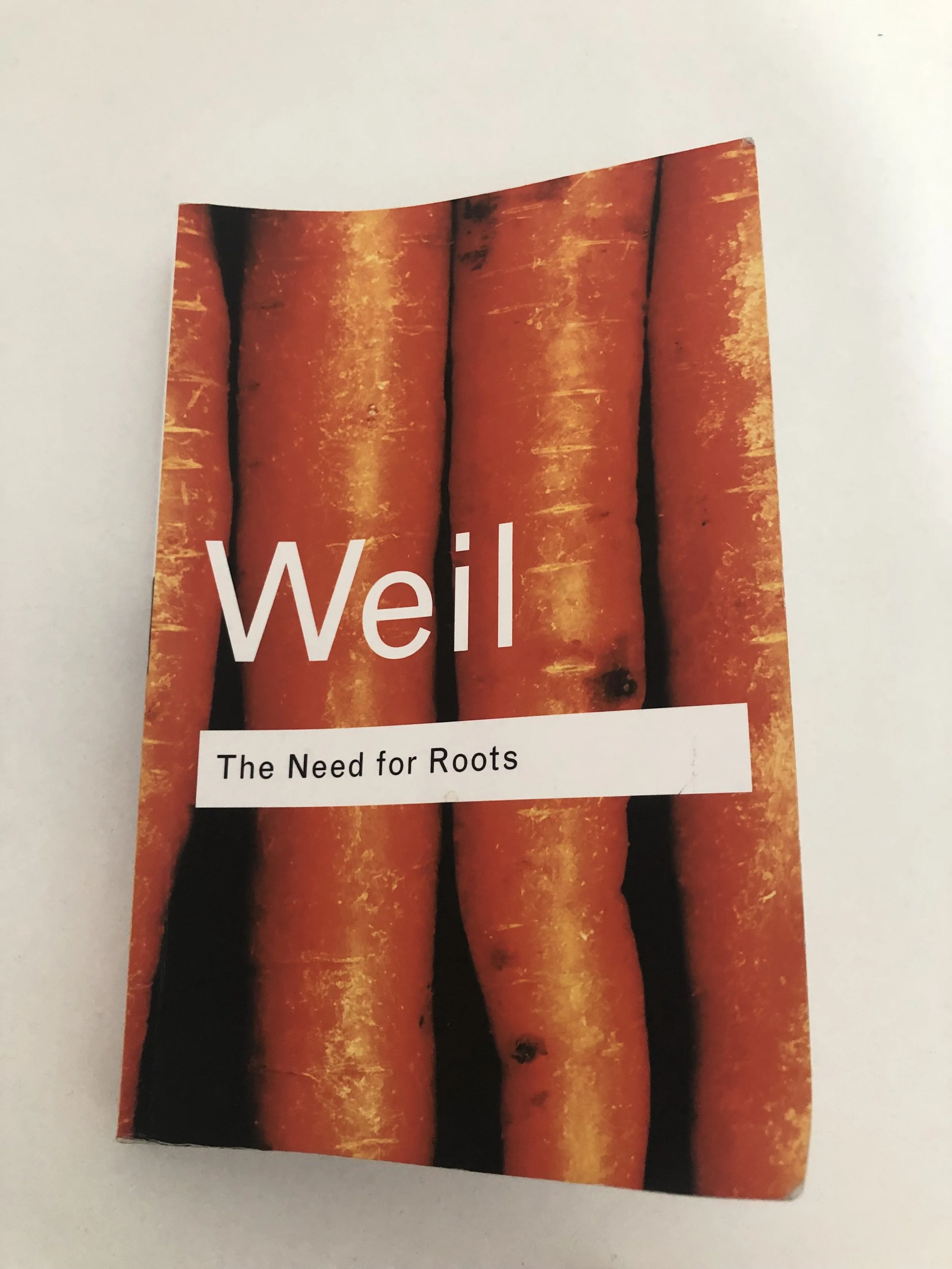

My copy of Simone Weil’s The Need for Roots. I picked it up in the London Review Bookshop when I was last in London. Sadly, I had to leave it behind in Croatia to make space in my suitcase.

On the back cover of Susan Sontag’s collection of short stories, I, etcetera, is a review from Michael Wood of the New York Review of Books: “The book not only confronts and explores the life which is traveled rather than lived, it records a life fully lived in the face of all such doubts.” The life which is traveled rather than lived. Or, you could say, a life without roots. It’s not that a life without roots isn’t fully lived, but it can make one feel fragmented.

I spent this past summer with Benjamin Moser’s biography of Sontag—it became my journal I wrote in it so much, my own biography. Moser identifies in Sontag’s life and work a distance between her mind and body that cannot be bridged, a desire to overcome the problem of the self. It’s this distance Sontag felt within herself that makes me feel close to her. She was concerned with her origins, even lied about them to control or, rather, find her truth. And I think Sontag’s search for truth in her origins is the same as my search for truth in the roots I want to put down. But what are these roots exactly?

Not my copy, I’m afraid. I had to finally leave it behind in London when I was in a rush to catch a plane for Ireland and couldn’t fit this massive work in my backpack. The sacrifice!

Around the time I wrote my last blog post about putting down roots, I happened upon Simone Weil’s The Need for Roots in the London Review Bookshop on Bury Place. It’s a beautiful little paperback with a photograph of large orange carrots on the cover. The title called out like an answer to a question I didn’t know I’d been asking myself—should I put down roots? Where? And how?

Another photo of my copy of Weil’s declaration of duties toward mankind.

I’ve been familiar with the French philosopher and activist’s work for some time, having first discovered Gravity and Grace while browsing the shelves of a used bookstore when I was 15. I’ll admit that I couldn’t grasp her work at the time (I still don’t, completely), but I couldn’t pass up the paperback with an outline of Weil’s face inked on the cover.

My copy is packed away somewhere in my storage locker. I must reread it!

Haunting—there’s no better way to describe it. I still have the book, a compilation of entries from Weil’s journals that capture her ideas about existence, God, eternity, and the self. A few years ago I read On the Abolition of All Political Parties, an essay in which Weil argues that true democracy can only begin where “party spirit,” where collectives formed based on self-serving interests, end.

In The Need for Roots, Weil diagnosis 20th-century civilization with “uprootedness,” defined as the loss of ties with the past and a dissolution of community. She wrote this treatise during World War II, which she didn’t survive, in an effort to lay out the “duties” we all have to mankind that must be met to feel rooted culturally, spiritually, politically. These duties are our roots, and they must be nurtured, according to Weil, in order for us to lead morally good and fulfilling lives.

The first part of Weil’s treatise establishes the needs of the soul, the eternal obligations we have in society: Order, Liberty, Obedience, Responsibility, Equality, Hierarchism, Honor, Punishment, Freedom of Opinion, Security, Risk, Private Property, and Truth. In order to regenerate France after the war, she proposed a society structured around these obligations, which she believed to be more essential than rights. For rights to be essential, Weil says, man must live amongst other men in society. But obligations are always essential, even when man is alone: “Rights are always found to be related to certain conditions. Obligations alone remain independent of conditions… The object of any obligation, in the realm of human affairs, is always the human being as such. There exists an obligation towards every human being, without any other condition requiring to be fulfilled, and even without any recognition of such obligation on the part of the individual concerned” (pp. 4-5).

“Rights are always found to be related to certain conditions. Obligations alone remain independent of conditions… The object of any obligation, in the realm of human affairs, is always the human being as such. There exists an obligation towards every human being, without any other condition requiring to be fulfilled, and even without any recognition of such obligation on the part of the individual concerned.”

Part I of Weil’s treatise outlines and defines the needs of the soul.

Reading Weil’s The Need for Roots at a moment when I realized that I don’t want a nomadic lifestyle helped me see my quest to put down roots in a more universal context. In my last blog post, I was focused on finding a place to be rooted to, on putting down roots somewhere. That’s why I wanted to get back to Spain at the end of my 90-day Schengen exile. But the time away showed me that putting down roots isn’t about leaving the United States or Spain or any physical place—it’s about finding what’s essential, about what I want to attach myself to. Symbolically, I’ve been stripping my suitcase down to what’s essential, keeping only what matters (I’ll write more about my suitcase in another post). Roots have weight, and I think it’s important that this weight not feel like a burden.

Now, there’s the question of what I am rooting myself to if not a physical place. I’ve come to like “attachment” over “rooted.” To me, attachment sounds less fixed. It’s fluid, I can move around if I need to. But I need roots to help me attach, to act as connectors. As Weil puts it, roots are the “needs of the soul,” and they don’t ground so much as connect. They allow one to move through many contexts without losing oneself. For me, this process of rooting and attaching is happening within. I’m getting clearer on what is essential about me, as well as a gap between my mind and body that needs to be bridged. I have always felt split and divided, and I suppose I’m really looking to become whole, to experience life as Maggie Entire.

I’ve started to define these roots that will allow me to attach my mind and body, so I can feel more rooted in my own life. My feelings of “uprootedness” have everything to do with living with a scattered self.

Space to simply be

This is the most crucial root. Finding space, making space is something I’ve been thinking about a lot. It’s not even that I want to be more intentional about how I spend my time, because I want time to not even be a factor. I want to lose track of time, to approach work I want to do in the way I want to do it. Maybe this space can never fully exist within capitalism, but I find myself experimenting with ways to make this space.

The space to be and feel most yourself is an abstract concept, an emotional sense more than anything tangible. In a capitalist society, it can be reduced to blank spaces in a calendar, which is all it’s been for me thus far. I’ve been experimenting with finding open space in my Google Calendar, space where my mind is free to wander.

But beyond my productive self, what is this space? What does it look like? What does it feel like? Would it still feel like space if I didn’t have to make room for it? Would it feel like freedom if I had nothing to be freed from? And is freedom really what I mean by space? I don’t think so. I picture myself floating, being able to move. To have space means to be fluid and present.

It’s difficult to be anything but paralyzed when you’re expected to do nothing but produce. When you’re either productive or nothing. It’s claustrophobic. There’s no time or room to simply be. What’s worse is that I’m not sure I would know how to just be. It will take time to become accustomed to the fluidity of space, to think in the moment rather than ahead to what needs to be done. But this is what the space to simply be is: It allows me to be present, so I can move.

Movement

I’ve been mistaking my need for movement with a need to be nomadic. But movement isn’t about living in different places and never feeling settled anywhere. It’s a need to move the body in purposeful ways, in ways that make me appreciate how my body functions and how this function is unique to me.

I must walk to feel settled within myself. I must spend time outdoors to close the gap between my mind and body, to bring them closer together. I must be anywhere but hunched over my desk. There’s a reason why hiking and long walks through city streets help me figure things out, whether it’s what I think about current events or a tough decision I need to make. Movement unifies my mind and body, which feels fragmented when I’m stagnant. When I sit for too long, it’s just my mind that’s working, going into overdrive, racing ahead of the rest of my body. A disconnection—my mind and body are out of sync without movement.

Mind-body connection

I can’t be rooted if my mind and body are fragmented, if a gap exists between them. Movement helps me connect them, but there’s a more profound separation I make between the two that I need to heal. I subordinate my body, treat it as an entity that can’t be trusted and must be disciplined. I don’t believe my body is controlled by my mind—I think it’s sculpted and created and refined by it. My body is my writing, a product that can be worked and reworked by my mind’s hand.

But this dichotomy drains life from my body and positions my mind as a force that gives it life. More meditation needs to be done to give them equal purpose. This meditation can take many forms: yoga, deep breathing, intuitive eating, silence, and solitude. Continued journaling and therapy will also help me continue to build and stabilize this bridge.

Creative spirit

My final root is creative spirit, which is essential for imagining the attachments I do and don’t want to have. This spirit drives me to live life creatively and passionately. I’m trying to attach myself to a life that matches this spirit, and this is the ultimate attachment I need to make. I have felt somewhat rootless because I haven’t prioritized fostering a connection between my life/work/desire and this spirit.

My creative spirit is what I’ve been referring to as my “European self,” or my truest self. While this spirit has flourished in Europe, it’s important for me to recognize that it doesn’t need Europe. As I’ve said throughout this post, finding the right place to settle isn’t as crucial as I originally thought. What is crucial to my creative spirit is identifying all my roots and nourishing them, so I can feel settled within myself.